Untangling the vocabulary of data and information modeling

The Terminology Jungle

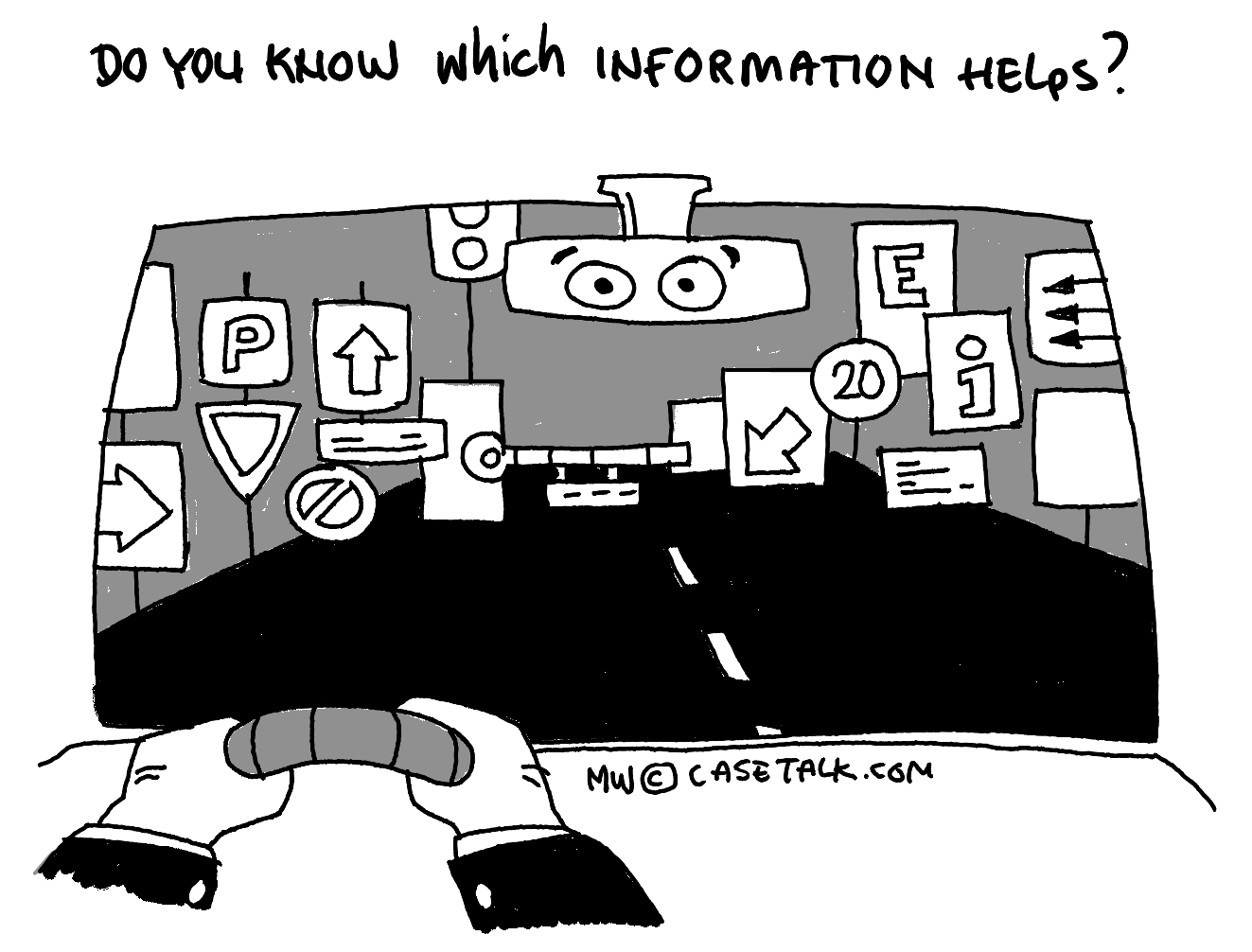

If you've spent any time in the data modeling space, you've likely encountered a bewildering array of terms: data model, conceptual model, logical model, physical model, concept model, semantic model, information model, fact-oriented model. These terms are sometimes used interchangeably, sometimes mean completely different things depending on who's speaking, and often cause more confusion than clarity.

This article aims to untangle these terms, trace their historical origins, and explain why the distinctions matter—especially as organizations grapple with integrating systems across departments and making sense of decades of accumulated data.

Data Model: The Umbrella Term

Before diving into the layers, let's establish the terrain. Data model is the generic umbrella term that encompasses the entire discipline of representing data structures and their relationships. When someone says "data model," they could mean anything from a quick whiteboard sketch to a fully specified database schema.

The term gained prominence in the 1970s with the rise of database management systems. Edgar Codd's relational model (1970) and Peter Chen's entity-relationship model (1976) established data modeling as a formal discipline. The traditional conceptual/logical/physical hierarchy that most practitioners know today falls squarely within this "data model" territory.

However, data modeling as traditionally practiced focuses primarily on structure: What are the entities? What are their attributes? How do they relate? The data itself—and more importantly, the meaning of that data—often remains a secondary concern.

The Traditional Three-Layer Architecture

Within the data modeling discipline, the most widely recognized framework divides the work into three layers:

Conceptual Model

The conceptual model emerged in the 1970s and 1980s as a way to capture high-level business concepts without technical implementation details. It answers the question: What are the important things in our business, and how do they relate to each other?

A conceptual model typically shows:

- Major business entities (Customer, Product, Order)

- Relationships between entities

- High-level attributes

Crucially, the conceptual model deliberately omits technical details like data types, keys, or normalization. The idea is that business stakeholders can review and validate a conceptual model without needing technical expertise.

Logical Model

Here's a crucial point that often causes confusion: the logical model is a diagramming style, not a specific data architecture. It's a notation for depicting structure—and that same notation can represent vastly different modeling philosophies.

The logical model adds structure to the conceptual model. It defines:

- Specific attributes for each entity

- Data types

- Primary and foreign keys

- Relationship cardinalities

What makes it "logical" is that it's technology-independent yet detailed enough for implementation. But here's what many practitioners miss: the logical model can be used to depict:

- Normalized models (3NF): The classic approach, eliminating redundancy through normal forms

- Dimensional models: Star and snowflake schemas for analytics, with fact tables and dimensions

- Data Vault models: Hubs, links, and satellites for historical tracking and auditability

- Entity-Relationship models: Traditional OLTP structures

Each of these represents a fundamentally different philosophy about how to organize data—yet all can be drawn using logical modeling notation. The diagram style is the same; the underlying architecture is completely different.

This is precisely why looking at a logical model alone doesn't tell you much about the meaning of the data. You might see a "Fact" table in a dimensional model (a very specific technical concept) or a "Hub" in a Data Vault model, but the diagram won't explain why those patterns were chosen or what business context they serve.

Physical Model

The physical model is the actual database design, optimized for a specific technology platform. It includes:

- Table and column names (often abbreviated)

- Indexes

- Partitioning strategies

- Storage specifications

- Performance optimizations

The physical model may denormalize structures that were normalized in the logical model, add technical columns (audit timestamps, surrogate keys), or restructure data for query performance.

Where Traditional Modeling Falls Short

This three-layer approach served organizations well when systems were built in isolation—one department, one system, one context. As Marco Wobben observes from decades of experience in the field:

"In the seventies, eighties, even nineties, a lot of systems were built for a specific purpose, for a specific department. Everybody knew the context. If I put 'customer' there, they all know what customer is."

The problem arose when IT proliferated. Computers appeared in every department, each system built in isolation with implicit context that was never documented. When organizations later tried to integrate these systems through data warehousing, they discovered a critical gap: the conceptual and logical models captured structure, but not meaning.

Consider the word "inventory":

- Sales says "we have three" (they already sold some)

- Purchasing says "we have eight" (they ordered more)

- Warehouse says "we have five on the shelf"

Everyone agrees on the definition of inventory—"the amount of things we have of a certain article"—yet they have completely different data. The traditional conceptual model would show an "Inventory" entity, but it wouldn't capture these crucial contextual differences.

Semantic Model and Semantic Data Model

Before exploring information modeling, it's worth addressing two related but distinct terms: semantic model and semantic data model. Despite their similar names, these terms occupy different conceptual spaces.

Semantic Model (Umbrella Term)

Semantic model functions as another umbrella term—like "data model"—that loosely encompasses any attempt to capture meaning alongside structure. It's used inconsistently across contexts:

- Sometimes it means a conceptual model with richer annotations

- Sometimes it refers to formal ontologies (RDF, OWL)

- In the Microsoft Power BI ecosystem, "semantic model" specifically means a dataset with defined relationships and measures

- In enterprise architecture, it often means a business glossary linked to data structures

The term's vagueness reflects an ongoing tension in the field: everyone agrees that capturing meaning is important, but there's no consensus on how to do it or what "meaning" even entails.

Semantic Data Model (Specific Technique)

Semantic data model, by contrast, is a much more specific term that sits outside the semantic model umbrella. It refers to a particular approach: a data model where verbs are attached to the relationships.

Instead of an unlabeled line between Customer and Order, the relationship is named "places" or "submits." The model becomes readable: "Customer places Order" rather than "Customer → Order."

This interpretation is particularly interesting because it represents a minimal but powerful step toward semantics: just adding readable relationship names makes models dramatically more understandable to business stakeholders. It's also a core principle in fact-oriented modeling, where every relationship must be expressible as a readable sentence.

Historically, the semantic data model concept emerged in the late 1970s and 1980s as researchers recognized the limitations of purely structural models. This movement gave rise to extended entity-relationship models, object-role modeling, and eventually ontology languages.

The distinction matters: "semantic model" is a fuzzy umbrella that can mean almost anything related to meaning, while "semantic data model" is a concrete technique—add verbs to your relationships so the model reads like natural language.

Enter Information Modeling

The term information model emerged to address this gap. Where data modeling focuses on how we structure the storage of data, information modeling focuses on how we talk about the data.

The key distinction:

- Data modeling asks: What tables, columns, and relationships do we need?

- Information modeling asks: How do people in the organization communicate about this data, and how do we preserve that communication?

An information model captures:

- Natural language expressions used by the business

- The semantic meaning behind data structures

- Contextual usage across different departments

- Business rules expressed in human-readable form

Information modeling recognizes that the same data may be used differently in different contexts, and that preserving this context is essential for long-term understanding.

Fact-Oriented Modeling: A Historical Perspective

Fact-oriented modeling (also called fact-based modeling) represents a specific approach to information modeling that developed primarily in academic circles from the mid-1970s through the early 2000s.

Origins and Dialects

The theoretical foundations were laid in the mid-1970s by researchers exploring how to capture business semantics more rigorously than entity-relationship modeling allowed. The core insight was radical: instead of starting with entities and attributes (type-level concepts), start with concrete examples of data—actual facts.

Three main dialects of fact-oriented modeling emerged:

NIAM (Natural Language Information Analysis Method) — The ancestor, developed by G.M. Nijssen in the 1970s at Control Data in Belgium. NIAM introduced the fundamental idea of grounding data models in natural language sentences populated with example data. It spawned two distinct evolutionary paths:

ORM (Object-Role Modeling) — Evolved from NIAM primarily through the work of Terry Halpin in Australia. ORM emphasizes logical rigor and formal constraint specification. It provides a rich graphical notation and has been implemented in tools like NORMA and earlier in Microsoft Visio. ORM excels at precisely capturing complex business rules and can generate normalized relational schemas automatically.

FCO-IM (Fully Communication-Oriented Information Modeling) — Also descended from NIAM, developed by Guido Bakema and others in the Netherlands. FCO-IM emphasizes capturing natural language and communication from the domain. Where ORM focuses on formal correctness, FCO-IM prioritizes the verbalization—ensuring that every element of the model can be read back as sentences that domain experts recognize and validate. This makes FCO-IM particularly suited for workshops with business stakeholders where communication alignment is the primary goal.

The philosophical split reflects a fundamental tension: Do we optimize for logical precision (ORM) or for communication with the business (FCO-IM)? Both share the same foundation—facts grounded in examples—but emphasize different aspects of the modeling process.

The Methodology

In fact-oriented modeling, you don't begin by saying "customer buys product" (an abstract, type-level statement). Instead, you say:

"Customer with customer number 123 buys product XYZ"

Where both 123 and XYZ are actual data—real examples that ground the discussion.

This seemingly simple shift has profound implications:

-

Disambiguation: When you use real data, you quickly discover that different people may use the same words but mean different things. The "inventory" problem surfaces immediately when you ask departments to provide actual numbers.

-

Constraint discovery: By asking questions like "Could Marco live in Utrecht AND New York at the same time?", you discover business rules that drive data structure. If the answer is no, city becomes an attribute of citizen. If yes, you need a linking table.

-

Identification clarity: You discover how entities are actually identified in different contexts. One system uses customer numbers; another uses email addresses. The fact-based approach makes this explicit: "My citizen can either be identified by first name and surname OR by email address."

Key Terminology

Within fact-oriented modeling, specific terms have precise meanings:

- Fact type: A classified pattern of facts (e.g., "city of residence" is the fact type for statements like "Marco Wobben lives in Utrecht")

- Object type: The concepts that participate in facts (citizen, city)

- Label type: The type for the data values as named by the business (first name, surname, city name)

- Role: How Label/Object types are playing a place in other Fact/Object types (first name in citizen, citizen in city of residence, ..)

- Population: The actual example data that illustrates a fact type

Concept Model vs. Conceptual Model

These terms sound nearly identical but refer to distinctly different things. The confusion they cause in meetings and documentation is substantial.

Conceptual Model

Conceptual model refers to any non-technical, non-implementation-oriented model. The term "conceptual" here means "abstract" or "not specifying what to build." A conceptual model captures business information and meaning without dictating implementation details like data types, storage structures, or platform-specific optimizations.

In the traditional data modeling hierarchy, "conceptual model" specifically refers to the first layer—a high-level entity-relationship diagram. But the term is broader than that: any model that focuses on business meaning rather than technical implementation is conceptual.

This leads to an important realization: a fact-oriented model is also a conceptual model. It models business information and meaning. It captures how people talk about data without specifying what database to build or how to structure the storage. In this sense, fact-oriented modeling is conceptual modeling—just with a more rigorous methodology grounded in natural language and concrete examples.

Concept Model (or Concepts Model)

Concept model (also called concepts model) is something entirely different: a model of concepts. It attempts to plot and relate concepts or terms within a context—showing how different terms in a domain connect to each other.

A concept model defines what terms mean and shows the relationships between them: "Customer" is a type of "Party," which can also be an "Organization." It's taxonomic and ontological in nature, closer to a glossary or taxonomy than a data structure.

Why the Distinction Matters

| Term | Meaning | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Model | Non-technical, non-implementation-oriented | Business meaning, not how to build |

| Concept Model / Concepts Model | A model of concepts/terms | Definitions and taxonomic relationships |

The traditional three-layer hierarchy uses "conceptual model" narrowly (entity-relationship diagrams), but the term properly applies to any model that stays at the business level. Fact-oriented models, information models, and even well-annotated entity-relationship diagrams are all conceptual in this broader sense—they describe what the business cares about, not how to implement it technically.

Why This Matters Today

The distinction between these modeling approaches becomes critical when you consider:

The Knowledge Evaporation Problem

With average job tenure at four to six years, organizational knowledge constantly evaporates. Traditional data models create schemas and diagrams, but as Wobben notes:

"There's not really a story there. A lot of architects and data modelers will reply with 'yeah, that's what I do in my head.' But does it leave your head? Does it get written down somewhere so that your colleague can take over?"

Information models—particularly fact-oriented models—preserve the narrative. They capture not just structure but meaning, in language that business stakeholders can read and verify.

The LLM Challenge

Large language models can generate plausible-sounding explanations of data, but they cannot verify whether those explanations match your organization's actual reality. Fact-oriented modeling, with its grounding in concrete examples, provides exactly the kind of verified context that keeps AI useful rather than hallucinating.

Technical Debt vs. Business Debt

Organizations accumulate not just technical debt (undocumented systems) but business debt (nobody knows what the data meant to the business anymore). The three-layer conceptual/logical/physical approach doesn't address business debt because it focuses on structure, not semantics.

From Information Model to Implementation

One powerful aspect of properly captured information models is that technical artifacts can be generated automatically:

- SQL databases with comments containing the original business language

- Test data drawn from interview examples

- Database views representing complete user stories

- Data Vault models, normalized models, or JSON schemas

The physical implementation becomes automatable when the semantic foundation is solid. As Wobben puts it:

"Having all the semantics and verbiage and examples, it makes it verifiable and readable by the business."

Data Outlasts Technology

Perhaps the most compelling argument for investing in information modeling comes from observing how systems evolve:

"I've seen systems where the database was designed with rigor and the software was developed three times over, but the database didn't change. Mainframe became Windows, became Internet, became mobile. The technology changed, the business processes changed—but the data itself didn't change."

This observation should give every organization pause. The data model you build today may outlive multiple generations of applications, user interfaces, and technology platforms. Investing in capturing not just the structure but the meaning of that data pays dividends for decades.

A Practical Summary

| Term | Focus | Key Question |

|---|---|---|

| Data Model | Umbrella term for structural representation | How do we represent data structures and relationships? |

| Conceptual Model | Non-technical, non-implementation-oriented | What does the business care about? (Broader than just ER diagrams) |

| Logical Model | Detailed structure (diagram style) | What attributes, keys, and data types? Can depict 3NF, dimensional, Data Vault, or other architectures |

| Physical Model | Implementation | How do we optimize for the target platform? |

| Semantic Model | Umbrella term for meaning-focused approaches | What do concepts mean? (Term used inconsistently across contexts) |

| Semantic Data Model | Specific technique: verbs on relationships | Can we read the model as natural language sentences? |

| Concept Model | Model of concepts/terms | How do terms relate taxonomically? |

| Information Model | Semantics & communication | How do people talk about this data? |

| Fact-Oriented Model | Grounded semantics (also conceptual) | What concrete examples illustrate our data usage? |

The Hierarchy of Terms

To visualize how these terms relate:

DATA MODEL (umbrella term)

├── Conceptual Model ──┐

├── Logical Model ─────┼── Traditional three-layer architecture

└── Physical Model ────┘ (structure-focused)

CONCEPTUAL MODEL (broader sense: non-technical, non-implementation-oriented)

├── Traditional ER-style conceptual models

├── Information Models

└── Fact-Oriented Models ← also conceptual! (business meaning, not implementation)

SEMANTIC MODEL (umbrella term for meaning-focused approaches)

├── Loosely: enriched conceptual models, ontologies, glossaries

└── Varies widely by vendor and context

SEMANTIC DATA MODEL (specific technique—outside the umbrella)

└── Data model with verbs attached to relationships

└── "Customer places Order" instead of "Customer → Order"

CONCEPT MODEL (model of concepts/terms)

└── Taxonomies, glossaries, term relationships

INFORMATION MODEL (communication-focused)

└── Fact-Oriented Model (grounded in concrete examples)

├── NIAM (ancestor)

├── ORM (logical rigor)

└── FCO-IM (communication focus)

└── Generates → Data Models (logical, physical)

The key insight: fact-oriented models are conceptual models—they capture business meaning without specifying implementation. But here's what makes them unique: by tying together meaning, semantics, examples, and precision, a fact-oriented model is conceptual yet precise enough to generate:

- Logical models (normalized, dimensional, Data Vault, etc.)

- Physical models (SQL schemas, JSON structures, etc.)

- Semantic models (ontologies, glossaries with relationships)

This generative power is remarkable. Traditional conceptual models are deliberately vague—they need manual translation to become logical or physical models. Fact-oriented models maintain business-level readability while capturing enough rigor that the translation can be automated. You get the best of both worlds: a model that business stakeholders can read and validate, yet precise enough to drive implementation.

The Logical Model's Flexibility

It's worth emphasizing: when someone shows you a "logical model," you need to ask what kind of logical model. The diagram style accommodates:

| Architecture | Purpose | Typical Use |

|---|---|---|

| Normalized (3NF) | Eliminate redundancy | OLTP systems, source systems |

| Dimensional | Optimize for analysis | Data warehouses, BI reporting |

| Data Vault | Track history, enable auditability | Enterprise data warehouses |

| Anchor Modeling | Extreme flexibility for change | Highly volatile domains |

All of these can be expressed in logical model notation. The diagram doesn't tell you why that structure was chosen—that requires documentation of the business context, which is precisely what information modeling and fact-oriented modeling provide.

Getting Started

For those interested in exploring fact-oriented and information modeling:

-

Start with a problem domain. There's always a problem to solve, an integration challenge to address. You can't just jump into the jungle and start describing insects on the floor.

-

Ground everything in examples. Don't accept abstract definitions. If someone can't give you a concrete example, they're likely outside their scope of expertise.

-

Tie language to data. Keep examples connected to fact types so you can transform models into any artifact while preserving original meaning.

-

Don't throw away the story. Whatever technical artifacts you generate, preserve the semantic context that makes them understandable.

Resources

- CaseTalk — Software tool supporting fact-based modeling

- "Just the Facts" by Marco Wobben (Technics Publications) — An overview for management, architects, modelers, and developers

- DAMA-DMBOK — Contains articles on fact-based modeling (improved in version 2)

- Wikipedia — Background on fact-oriented modeling

Changes

- Rémy Fannader Recommended to make the difference between conceptual and concepts models more specific.

-

Jessica Talisman Remarked ontologists and ontologies refer to concept models, not semantic models.

In a world where everyone's chasing the next silver bullet, there's wisdom in an approach that starts with a simple question: Can we talk to each other, and are we writing down how we do that?